The central characters are two women in their forties going through a mid-life crisis: Lydia Tár, the creation of Todd Field the film’s director & writer, and Empress Elisabeth, recreated through the modern lens of Austrian director Marie Kreutzer. Although living more than a hundred years apart in very different social settings from very different backgrounds they share something that not only destabilizes their lives but destroys it.

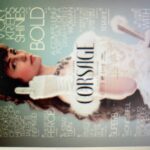

Kreutzer’s reinterpretation of the historical Empress Elisabeth who has attracted ongoing attention in film, theater and television over countless years has caused some controversy. Disregarding the traditional rules of the biopic the film disappointed those who had hoped to find the drama and turmoil of the historical Empress – and her life was full it – but delighted those who thought Kreutzer’s modern interpretation – often compared with Princess Diana in Pablo Larrain’s Spencer, transcends eras. Corsage focuses on the 40th year of Elisabeth’s life – not an obvious turning point but more the extension of daily routines and frustrations. Subjugated by a husband and his court she detests, Elisabeth continues her daily beauty protocol she seems to have imposed on herself with baths, exercises, measuring her waistline, eating barely anything to make sure the corsage won’t need to be loosened. Though she lives in luxury and is free to move around her castles, explore languages, science, literature, follow her objects of desires – from riding instructor to cousin King Ludwig of Bavaria – she wants more. She feels trapped, suffocated because the dictates of the court demand of her only one thing – to represent at the side of her husband with what she is famous for: Beauty. Kreutzer’s film is a delicate work of contradictions that comes to live through the nuanced performance of Vicky Krieps. She masterfully shows the two sides of Elisabeth, a decoration piece and a defiant non-conformist who sticks out her tongue or gives the finger – modern acts of insurrection that the director added to make a timeless statement about women’s repression. However, Krieps’ empathetic performances does all that – she did not need the tongue and the finger and the songs. Elisabeth is suffocating in a golden cage with only one door left open to escape to freedom. To delete all traces she cuts off her famously long hair, fits up a doppelgänger and introduces a lover to the emperor. The opening shots of the film show Elisabeth in a bathtub holding her breath under water for a long time – practicing diving or drowning? The final scene is a dive into the deep with no return. (The “real” Empress Elisabeth was assassinated in 1898 by an Italian anarchist at age 61. Her only son Rudolf died in 1889 at age 31 in a suicide pact with his mistress.)

Only a few women conductors have succeeded in the male dominated classical music world, even fewer have positions in first class orchestras, and no woman ever has had the leading position at the Berlin Philharmonic – except Lydia Tár, who broke the glass ceiling. Ambitious, talented, compulsive, charismatic she worked her way up from humble beginnings to the top and while bathing in fame and success the clock started ticking. Both films, Corsage and Tár, focus on the 40th year of their protagonist’s life, and both women stumble over the hurdles that come with fame and privilege. We meet Tár on the conductor’s podium in Berlin rehearsing Mahler’s fifth symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic. She is in control of every bar like great conductors are. However she is more than a conventional conductor – she is a woman and she is going through a crisis. She can not communicate with her students, they seem live in a different orbit. She has no time for her daughter, resolves her conflicts like all others by showing off her frosty omnipotence. Tár’s wife is concert master in the orchestra, a powerful position she had before Tár was hired. However both their professional and personal relationship seems to be steered by the baton of the music director. The turning point arrives when a previous conducting student accuses Tár of a sexual relationship that has destroyed not only her career but even her life. Tár denies any wrong doings in this and other hints at love affairs with former students. The film never reveals crucial events, blurs or eliminates details. A calculated measure of doubt cast throughout the more than two hour long movie will hardly turn the protagonist into a sympathetic victim. While the counter culture and the courts pronounced her guilty the predator on the loose pursued her next object of desire. But Tár survives the downfall. Banned from the world of classical music she finds an orchestra in a far away Asian country where she conducts what she detests most – kitschy film music.

What inspired Todd Field to create Lydia Tár? Why did he set the story in the concert hall of one of the most prestigious orchestras on the globe and not in Silicon Valley or the White House? Todd’s knowledge or insight in the classical music world could not have been the driving force – too much in the film does not make sense. And Tár, a failed music director, will not be the role model for young women with an eye on a leading post in the top ten orchestras. However Tár will stay with us in Cate Blanchett’s powerful interpretation of a woman in crisis. Omnipresent in every shot Blanchett shines – with an Oscar in close reach.